In this post, we will look how concepts are actually lenses, and how this helps us better understand morality. Part of the case will include how concepts are specific sets of criteria that narrow options down, and make it possible for us to observe, understand, and act with better precision. We will also cover what the largely unrecognized function of using lenses for decision-making is about, and why morality is justified on a basis that draws from concepts being lenses. In addition, justification for Sam Harris’* Moral Landscape position about thriving being morally good will be presented, along with lens-based insight on how thriving helps with validating or invalidating individual morals. We will also cover how we can use this understanding of lenses to help us with better moral decision-making.

(*I’m editing after posting, in particular because a recent incident was just called to my attention. I must make a point of saying that Harris is being credited for a portion of a specific contribution that was published on morality, but is not endorsed. Please also visit the link to learn more.)

Reviewing the Organizing of Our Thoughts and Our Belongings

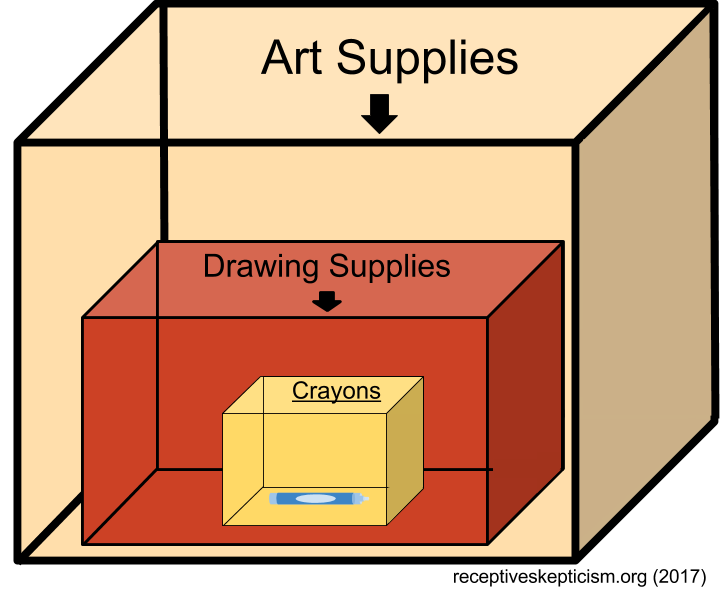

Previously, I showed how we organize our thoughts like we organize our stuff. Grouping everything into each smaller subset, (boxes in this case), helps us narrow focus to what needs finding. And this is because, as I illustrated in that last post, we process our thoughts by narrowing down focus. Pictured above, out of a very broad group, called “art supplies”, a sky blue crayon narrows focus down to just itself. The box labeled “Drawing Supplies” excludes anything not for drawing, and the box for “Crayons” excludes anything not a crayon. Then “sky blue” rules out all other crayons in the crayon box. Through this post, keep in mind how excluding happens through organizing. Also, note how we have an easier time keeping each set and subset in mind, when it comes to our stuff, as opposed to our thoughts. It’s easy to see that we have a large box of art supplies, and in it, a smaller box for “drawing supplies”, inside of which, lies the box “crayons”. Importantly, we don’t usually forget the sky blue crayon is an art supply, even though it is inside of two boxes. Nor do we forget that it’s a drawing supply.

The Relationship of Concepts

The Relationship of Concepts

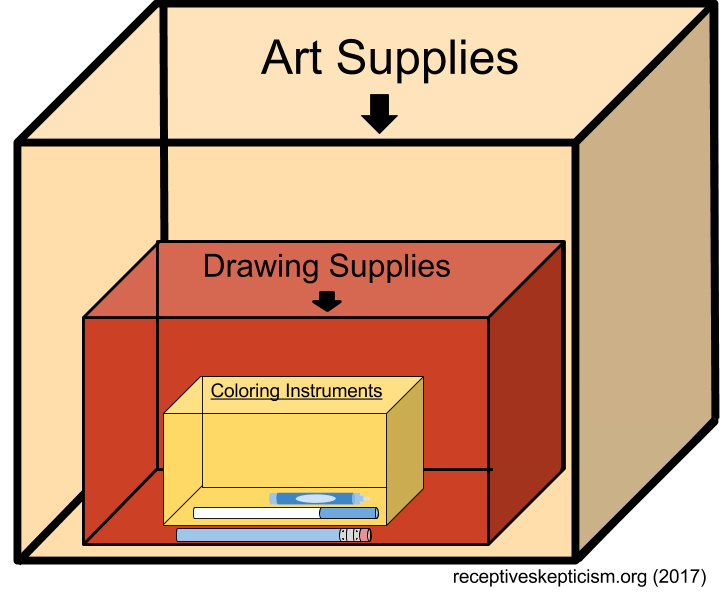

When we organize our stuff, we then view it from how we see the groupings should be done. That way of seeing the groupings is our organizational lens, and will be the way we access whatever we organized. If we replace the crayon box with a “coloring instruments” box, we changed the organizational lens on what belongs in the box, and now other coloring instruments also belong in the box. If there’s a sky blue marker, for instance, it then shares the same organizational space as the sky blue crayon.

Our organizational lens develops from conceptualizing items by location, from a particular point in time and space. The organizational lens is what we conceptualize. All concepts are sets of inclusion and exclusion criteria that fill that role of organizing to exclude options. This excluding serves to narrow focus, and provide a precise view on whatever is being viewed. The order we use them, changes the way things are organized. Whenever we add a new lens, it adds a new set of criteria, which further limits what we can work with in our deliberating.

Looking at Concepts From the Lens View

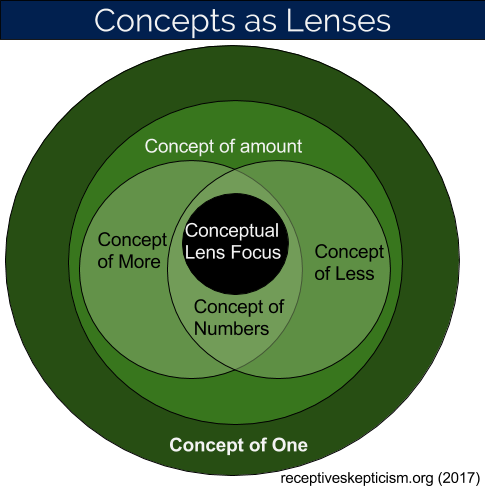

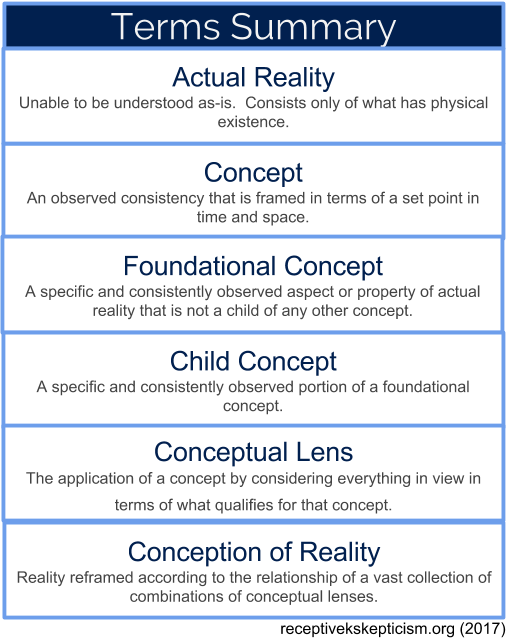

Any human view of reality is based from our set point in time and space, and all concepts develop from observed consistencies discovered from within that view. To help with understanding concepts as lenses, we can focus in by breaking the larger subject down by the terms below. This will also keep the relationship of lenses used together to a similar level of clarity as that of the relationship of the boxes used together in the art supplies example:

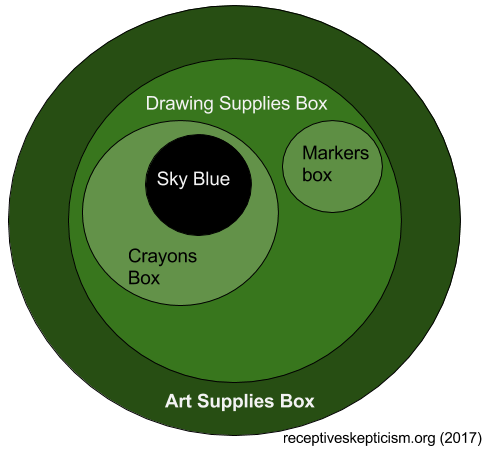

Let’s change the format to the normal way logic is diagrammed, so that we can enable a look at concepts as nested criteria in the same way we looked at the box as nested criteria earlier. We will also add a “Markers” box:

Concepts are lenses of exclusions for translating reality in a way that makes sense for the human thought process. The exclusions help for zooming in to a more precise view, as we just did on this topic. Some concepts are foundational concepts, while other concepts narrow focus to explore separate aspects within foundational concepts.

Concepts are lenses of exclusions for translating reality in a way that makes sense for the human thought process. The exclusions help for zooming in to a more precise view, as we just did on this topic. Some concepts are foundational concepts, while other concepts narrow focus to explore separate aspects within foundational concepts.

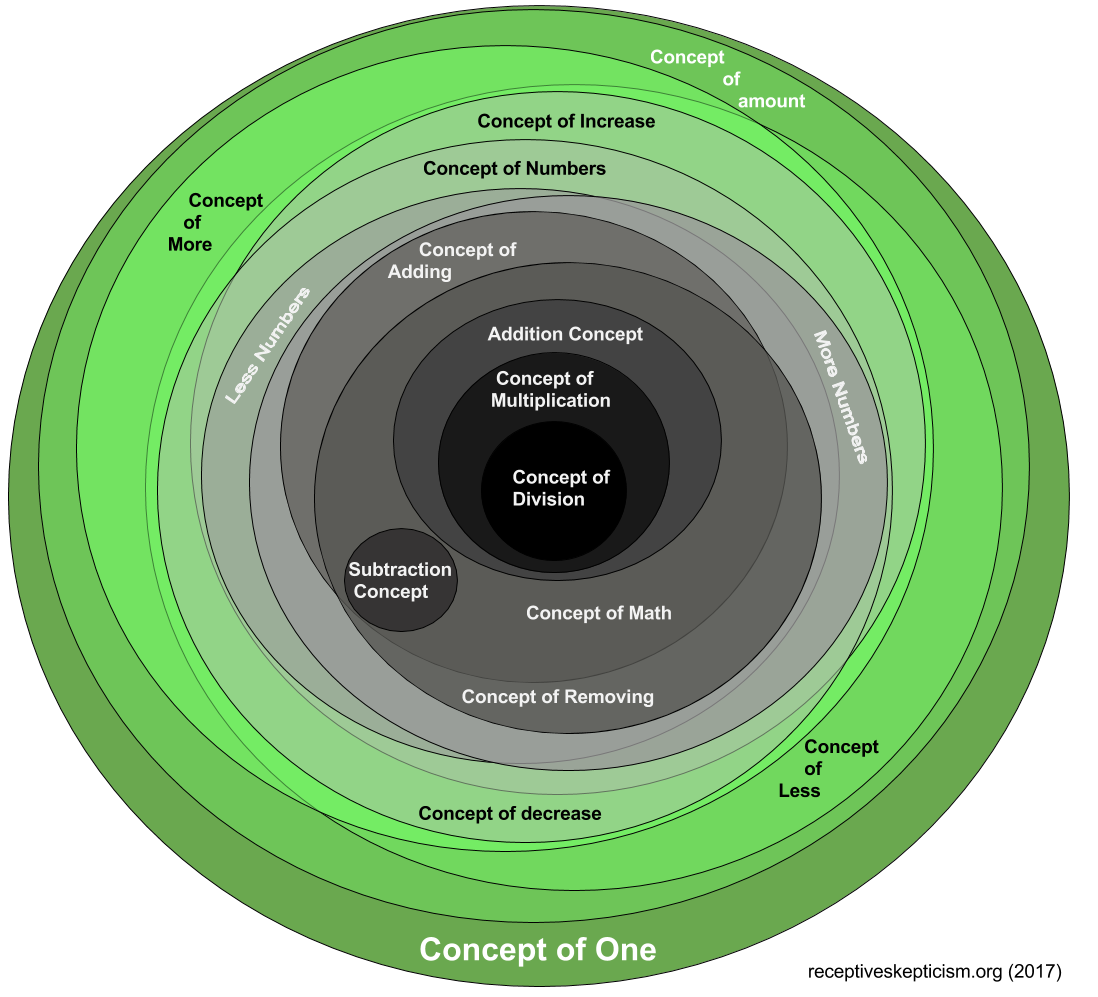

Arriving At Math Through Concept Lenses

The relationship between “foundational” and “child concepts” is easier to demonstrate by exploring the foundational and child concepts of math. From the concept of “one” (see the image above), we can have the concept of “amount”, and from there, the concepts of “more” and “less”, and from within “more” and “less” we have “numbers”, and so on. Everything beyond that is grounded in the foundational concept of “one”, and that foundational concept is grounded in what we consistently observe in reality about objects. Just like the crayon mentioned earlier is a kind of art supply, any subset “child concept” is just a type of the foundational concept and any “child concept” from which it is developed. By that nature the child concept is grounded to reality through any foundational concept it resides within. In the image below, you can see the process continued from “one” all the way to the math concept of “division”.

Morality From the Concept Lenses

Morality From the Concept Lenses

Because concepts are exclusion criteria, the more the order of sets and subsets that make up the concept is uncovered, a more precise use of the concept is found, because whatever is not excluded still falls within the precise use of the concept. We only need to uncover what is excluded to understand a concept accurately. Let’s look at an example of concepts as lenses in terms of morality, and in particular, using key exclusions to solve the moral question of whether we should steal or not:

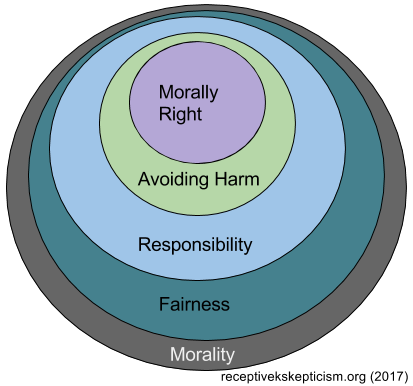

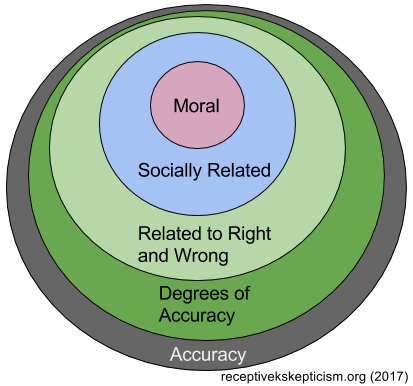

Morality is a type of social concern, which is a kind of right and wrong related to social concerns, and right and wrong scales are in the category of degrees of accuracy, which is enabled by organizing groups by accuracy. Not every kind of right and wrong relates to social concerns, and not every category related to social concerns must involve right or wrong. Viewing from the standpoint of accuracy, enables grouping by categories relating to it, and having categories specific to accuracy allows for the category of viewing from the lens right and wrong. And not every right and wrong has to do with morality, as math mistakes don’t, but organizing from within the lens of right and wrong allow for the lens of socially right and socially wrong. Knowing this, we can now move on to specific morals, and the question of stealing.

Applying Awareness of Concept Relationships to Moral Questions

Now we can look at the moral concepts. Fairness is a moral concept. If we add that lens, we only include whatever is fair. If we add the lens of whatever is responsible, we now only include whatever is fair and responsible, for which a smaller set of actions qualify. We now can find ourselves determining if we should steal on the basis of if the theft is fair and socially responsible. Stealing rarely is morally correct, even in many cases when the ownership is unfair, as it could have some negative consequences related to harm of others.

Reasons Morality Is Justified

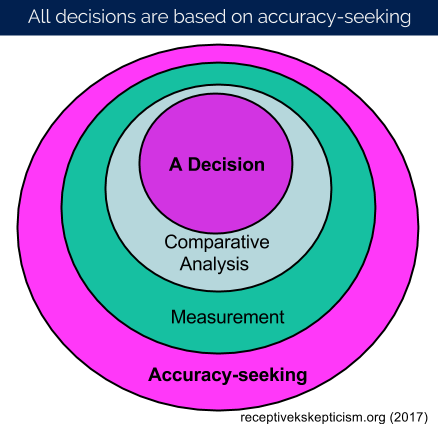

Just because we can make a lens doesn’t mean that lens is any good to use, though. We still need to justify the concept of morality as a valid type of foundational concept for it to be used as a lens (just like the concept of “one”), for epistemological reasons. Otherwise, morality could just be something that seems to work the problem out correctly, when it actually doesn’t. There are two reasons that justify morality, the first is because it’s grounded to reality as a valid form of accuracy seeking. The second reason is because we have no alternatives other than accuracy seeking, as even deciding not to decide fails to provide a means to avoid accuracy-seeking actions. This is because that would still involve a decision. Like the crayon is a type of art supply, a decision is a type of accuracy-seeking.

Decision is a comparative analysis, which is a kind of measurement and measuring is for accuracy. Even deciding not to decide is an accuracy-seeking action! And there being no alternative against accuracy-seeking in anything we do, justifies the morality lens, because deciding is a kind of accuracy–seeking. As deciding to avoid accuracy-seeking it isn’t really avoiding it, nothing competes against accuracy-seeking. All that we can do is perform good quality accuracy-seeking, or poor quality accuracy-seeking.

Decision is a comparative analysis, which is a kind of measurement and measuring is for accuracy. Even deciding not to decide is an accuracy-seeking action! And there being no alternative against accuracy-seeking in anything we do, justifies the morality lens, because deciding is a kind of accuracy–seeking. As deciding to avoid accuracy-seeking it isn’t really avoiding it, nothing competes against accuracy-seeking. All that we can do is perform good quality accuracy-seeking, or poor quality accuracy-seeking.

Enhancing Harris’ Thriving Principle and Validating Specific Morals

A broad concept like morality is fairly easy to justify as a valid lens, but people are pretty divided when it comes to the child concepts, i.e., any individual morals produced from the lens of the broad concept. But this is where I see the work of Sam Harris, in his book “The Moral Landscape” filling the rest in. Harris appears to be aware that morality is something valid. He invokes imagery of a landscape with high and low areas to help illustrate the concept. The main thrust of his case is that we can develop a gist of right and wrong based both on recognizing extremes, and seeing how consistent thriving related to a moral helps in telling us a moral is valid.

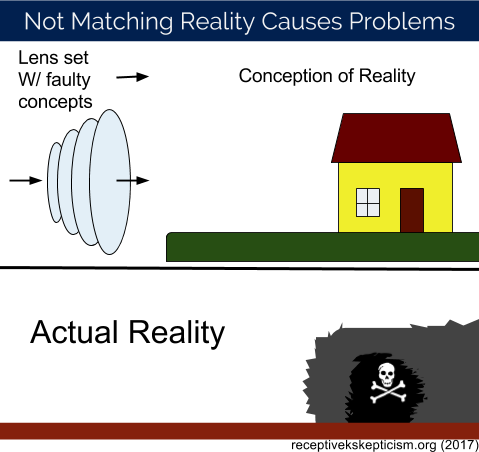

I would contend from a lens-based perspective, that the thriving mentioned by Harris is a decent measure, since concepts mapped to reality produce decisions aligned with reality. Alignment to reality makes enables concepts to work in the range of contexts the lens conveys they apply, whereas invalid concepts are likely to have major points of failure. Points of failure will be at places where reality is least aligned to the lens. For example, if a concept says something is safe when it’s dangerous, using the concept will lead to danger. Any new concepts developed from from a faulty lens to begin with, will have even more places where they fail to align with reality. The more other lenses focus in on a smaller aspect of any invalid parent concept, the more likely a critical failure to represent reality shows up.

Knowing where a concept comes from, and essentially where it is going (on the basis of what lenses are used to look from inside of it), helps us. We are then able to better utilize these concepts with clarity, and see where our understanding of the concepts may have flaws. Knowing what each concept is ultimately a type of lens of, can help us better avoid losing the end from within the means. A major example of this is that the ultimate end of what drives us to choose is accuracy, but that has been lost amongst the means of values. But personal values, like anything decision-related are developed to facilitate accuracy, and a value failing to facilitate accuracy is a malfunctioning one.

Conclusion

So right and wrong aren’t as arbitrary as some would have you believe. It is part of a set of tools with one purpose, to aid us in accuracy seeking. This also reveals nothing has anything other than malfunction-related value if it doesn’t facilitate accuracy-seeking activity. Choice, and freedom find their value in facilitating accuracy-seeking. This opens the door to for instance, circumventing freedom when accuracy grows too poor, and still having best interests in mind. We can recognize that freedom is a means to an end, and only matters in what it facilitates. So to practically apply this awareness, we can now justify not respecting a person’s desire to commit self-harm if in a state of psychiatric emergency. Freedom matters when it facilitates accuracy. If a person has freedom, and a more intimate understanding of circumstances that affect the situation, then they are more likely to succeed in accuracy seeking. If our sky blue crayon suddenly lost capability to function as an art supply, we wouldn’t be able to use it for coloring anything sky blue, or for any art. Similarly, with psychiatric emergencies, freedom is no longer a valid means to the end it facilitates, accuracy. What is best for a situation is based on the specific particulars, so what this lens-based understanding ultimately justifies for us, is circumstance and particular-specific objective morality.

John Kelly (Author)

Gianpaolo Merello Garbarino (Copy Editor)

Receptive Skepticism (2017)

Hi John, Thanks for you response to my comment on your ‘avoiding absolutes’ post.

I think I get the gist of what you’re trying to say here, but it does not always seem clear. The way I would put it is that moral judgements are always trying to address a condition of some kind, and thus the extent to which they address that condition (or, on the other hand, are interfered with by absolutism) is a way of assessing the justification of the moral judgement.

However, I’m concerned about your use of Sam Harris, in whom I see a lot of dogmatic assumptions. Here’s a link to my review of ‘The Moral Landscape’, in which I try to explain the weaknesses in his approach. http://www.middlewaysociety.org/books/ethics-and-politics-books/the-moral-landscape-by-sam-harris/

My review is quite complex and detailed, but to try to zoom in just on one take-away point that applies to your writing here, I’d say it’s that it focuses far too much on analysis to the exclusion of synthesis. Ethics depends more than anything on our awareness of alternative ways of thinking to the one’s we might initially assume: but philosophical or conceptual analysis of ethics far too often simply assumes one set of unquestioned assumptions about what ethics consists in, and then continues to expand on the implications of that view. To produce anything that’s adequate to people’s moral experience, I think you need much more acknowledgement of the limitations of your own moral standpoint, and more of an attempt to learn from the alternative approaches. As in your previous post, I also think that the diagrams are carrying far too much weight, almost as an end in themselves, and the assumptions around the diagrams are insufficiently explained.

Hi Robert. Thanks for the feedback, and you may have the same objections after clarification, but I think the gist you gave doesn’t sound right for what I meant. In a nutshell:

I see it as there being two factors in justifying morality:

One is that morality is a concept that finds validity in that it is grounded to reality, and the other is that we can only base our decisions on “accuracy-seeking”, where such accuracy-seeking relates to the navigation of reality.

I worked to explain those points by covering that concepts work like lenses, and those lenses focus in on what’s left within the narrowed set of criteria allowed by each concept involved. The diagrams are to try to explain it in a way that’s easier to see, but not meant to be complete. Basically though, the idea is that by understanding how concepts work as sets of criteria, we can then better understand how concepts join together under a decision-making lens. But this is just saying we can take that route to a better outcome, it isn’t meant to say what each step is along that way. I give examples, but they aren’t meant to be comprehensive either.

Is that similar or is it different to what you were getting out of it? I also wonder if you are seeing some of the things that are connected, but I didn’t really focus on conveying too?